In de afgelopen twee jaar zijn diverse rapporten verschenen van Europol (iOCTA (2024, 2025), SOCTA 2025, AI and Policing), de Politie (over AI en fraude), samen met het Openbaar Ministerie (eerste jaarbeeld), de UNODC (rapport), de AIVD (over AI en cybersecurity), het NCSC NL (o.a. het Cybersecuritybeeld Nederland 2025) en NCSC UK (onderdeel van GHCQ) over de invloed van AI op (cyber)criminaliteit en cybersecurity.

Het valt mij in de rapporten op dat op basis van incidenten soms grote conclusies worden getrokken. Toch is het belangrijk om de gesignaleerde trends op een rij te zetten. In deze blog vat ik daarom een aantal van die ontwikkelingen samen. De vijf trends heb ik zelf geselecteerd. Na het lezen heb ik voor deze tekst gebruik gemaakt van Copilot Researcher en Notebook LM. Een automatisch gegenereerde podcast is hieronder te beluisteren.

1. Verlagen van drempels voor criminaliteit en de versterking van cyberaanvallen

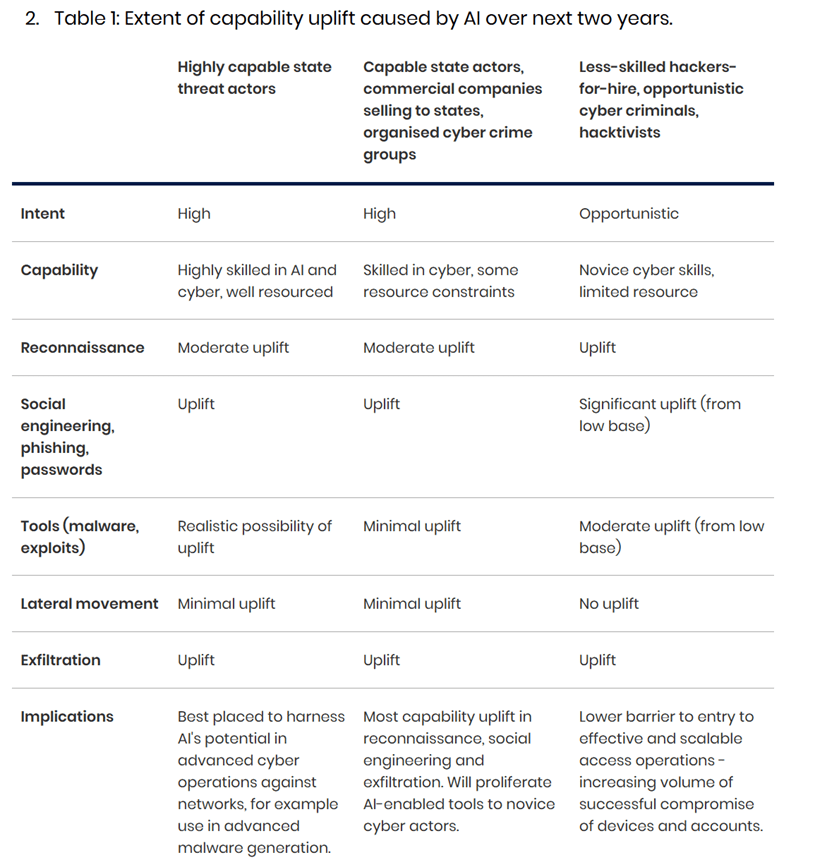

Criminelen zetten AI in om cyberaanvallen sneller, groter en effectiever te maken. Het Britse National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), onderdeel van GCHQ, waarschuwde in 2024 dat AI de omvang en impact van cyberaanvallen vrijwel zeker zal vergroten in de nabije toekomst. Dit komt doordat AI de benodigde technische kennis verlaagt en aanvallen automatiseert. Zie ook de tabel op The near-term impact of AI on the cyber threat – NCSC.GOV.UK.

Door generatieve AI kunnen ook onervaren of minder technisch onderlegde daders geavanceerde aanvallen uitvoeren. AI-modellen genereren bijvoorbeeld phishing-teksten en malwarecode waardoor de drempel voor nieuwe cybercriminelen daalt. Fraude en kindermisbruik worden vaak expliciet genoemd als domeinen die “bijzonder waarschijnlijk” door AI-gebruik zullen intensiveren. Europol signaleerde al in 2020 dat AI kan worden ingezet voor slimme wachtwoordkrakers, CAPTCHA-bots en gerichte social-engineeringaanvallen. Deze voorspellingen zien we nu werkelijkheid worden, met steeds geavanceerdere phishingaanvallen en door AI gegenereerde malware.

Daarnaast ontstaan illegale diensten waarbij cybercriminelen generatieve AI als betaalde dienst aanbieden. Volgens NCSC UK, de Organised Crime Agency (NCA) en Europol ontwikkelen kwaadwillenden eigen AI-tools en verkopen zij ‘GenAI-as-a-service’. Deze trend sluit aan bij de eerder gesignaleerde “vermarkting” van cybercrime-tools (zoals ransomware-as-a-service) in Europol-rapporten. Ook het UNODC-rapport uit 2024 signaleert dit fenomeen voor fraude en oplichting.

De beschikbaarheid van dergelijke tools, ook in kwaadaardige varianten op het dark web zonder ‘guardrails’, verlaagt de drempel voor cyberactoren zonder diepgaande technische vaardigheden. Criminelen gebruiken LLM’s om scripts te ontwikkelen voor phishingmails of websites voor gegevensdiefstal. Het groeiende ‘phishing-as-a-service’-aanbod weerspiegelt de automatisering van deze aanvalsvector.

2. Georganiseerde criminaliteit en AI

Veel van bovenstaande ontwikkelingen komen samen in de georganiseerde misdaad. Het SOCTA-rapport 2025 stelt dat criminelen AI als “onderdeel van hun gereedschapskist” beginnen te gebruiken. Klassieke activiteiten zoals drugshandel convergeren met cybercriminaliteit. Grote criminele groepen investeren in online fraude en datadiefstal naast hun traditionele handel. Zie eerder ook deze samenvatting van het SOCTA-rapport.

Europol signaleert ook vermenging met statelijke actoren. Criminele netwerken kunnen gegevens stelen voor staten door in te breken in beveiligde systemen. Deze informatie kan worden gebruikt voor spionage, economische voordelen of chantage. Daarnaast spelen deze netwerken een sleutelrol in desinformatiecampagnes, waarbij nepaccounts, trollen en gemanipuleerde nieuwscontent worden ingezet om democratische instellingen te ondermijnen.

Criminele organisaties misbruiken corruptie om vervolging te vermijden, onder meer door het omkopen van politie en justitie. Digitale trends versterken dit fenomeen: corrupte contacten worden online geworven, betalingen verlopen via cryptovaluta, en personen met toegang tot digitale systemen zijn belangrijke doelwitten. Netwerken gebruiken versleutelde communicatieplatforms zoals EncroChat en Sky ECC, maar ook reguliere apps om te rekruteren, handelen en betalingen te regelen.

Geweld wordt steeds vaker als dienst aangeboden (‘violence-as-a-service’), gefaciliteerd door online platforms en versleutelde communicatie. Jongeren worden actief gerekruteerd voor cyberaanvallen, drugshandel en als geldezel, vaak via sociale media en met verleidelijke tactieken zoals gamificatie. Technologie speelt ook een rol in traditionele misdrijven: online werving voor mensenhandel, wapensmokkel en illegale streamingdiensten. AI en 3D-printing vergroten de toegang tot vuurwapens en maken productie van vervalste medicijnen mogelijk. Digitale piraterij en online verkoop van illegale geneesmiddelen blijven groeien, ondersteund door anonimiserings- en cryptotechnieken.

Ook de UNODC signaleert hoe online gokken, grootschalige oplichting en witwassen van cryptocurrencies samenkomen in één ecosysteem, aangejaagd door AI-tools. Dit leidt tot een “criminele dienstverleningseconomie”, waarin phishingkits, valse documenten en AI-gegenereerde propaganda worden verhandeld. De VN noemt Zuidoost-Azië een proeftuin voor AI-gedreven criminaliteit. Scam-centra rekruteren jonge mensen onder valse voorwendselen en dwingen hen om samen met AI-systemen slachtoffers op te lichten. AI automatiseert een groot deel van het werk, terwijl mensen geloofwaardige interacties onderhouden.

Ook de AIVD constateerde in 2024 (‘Versterkte dreigingen in een wereld vol kunstmatige intelligentie’ .pdf) dat AI door iedereen kan worden gebruikt voor het maken van malware en phishingberichten, wat de dreiging door niet-statelijke actoren vergroot. Het SOCTA-rapport noemt ook hoe criminele organisaties door staten worden ingezet voor sabotage van kritieke infrastructuur, informatiediefstal en cyberaanvallen. Een van de belangrijkste manieren waarop zij bijdragen, is via ransomware-aanvallen op kritieke infrastructuur, bedrijven en overheidsinstanties. Deze aanvallen genereren niet alleen financiële inkomsten – vaak via cryptovaluta – maar dienen ook om tegenstanders te ontwrichten door essentiële diensten lam te leggen, chaos te creëren en het vertrouwen van het publiek te ondermijnen.

Een concreet voorbeeld is de cyberaanval op de Nationale Politie in september 2024 door de waarschijnlijk staatsgesteunde Russische groep LAUNDRY BEAR (zie deze advisory report .pdf).

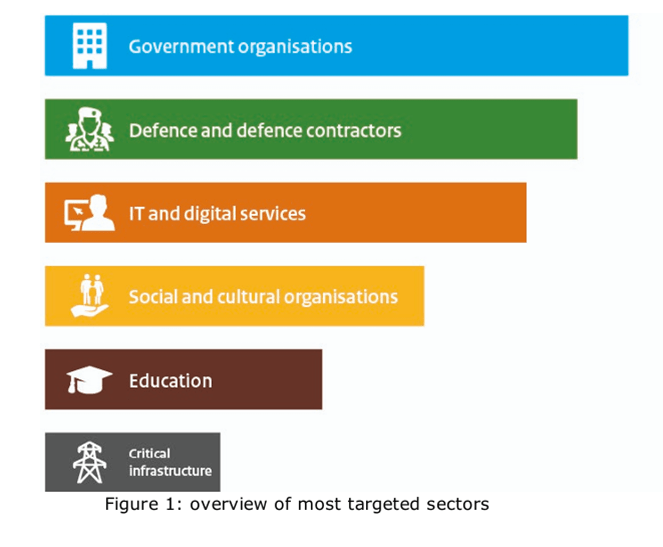

LAUNDRY BEAR richt zich, net als andere Russische cyberdreigingsactoren, voornamelijk op landen die lid zijn van de EU of NAVO. De groep valt vooral organisaties aan die relevant zijn voor de Russische oorlogsinspanningen in Oekraïne, zoals defensieministeries, krijgsmachtonderdelen, defensiebedrijven en EU-instellingen. Ook ministeries van Buitenlandse Zaken en andere overheidsorganisaties behoren tot de doelwitten. Naast Europa zijn er aanvallen waargenomen in Oost- en Centraal-Azië. In 2024 voerde LAUNDRY BEAR aanvallen uit op defensiecontractanten, luchtvaartbedrijven en hightech ondernemingen, waarschijnlijk om gevoelige informatie te verkrijgen over wapenproductie en leveringen aan Oekraïne. De groep lijkt kennis te hebben van militaire productieprocessen en probeert technologieën te bemachtigen die door sancties moeilijk toegankelijk zijn.

Naast militaire en overheidsdoelen richt LAUNDRY BEAR zich ook op civiele organisaties en commerciële bedrijven, vooral in de IT- en digitale dienstensector. Deze netwerken bieden vaak indirecte toegang tot overheidsinformatie, waardoor ze aantrekkelijk zijn voor spionage. Verder zijn aanvallen vastgesteld op NGO’s, politieke partijen, media, onderwijsinstellingen en kritieke infrastructuur, vrijwel zeker met spionagedoeleinden. In vergelijking met andere Russische actoren heeft LAUNDRY BEAR een hoge succesgraad. De meest getroffen sectoren zijn: overheidsorganisaties, defensie en defensiecontractanten, IT- en digitale diensten, sociale en culturele organisaties, onderwijs en kritieke infrastructuur.

3. AI in fraude en oplichting

Criminelen misbruiken deepfakevideo’s, -audio en -afbeeldingen om vertrouwen te winnen of druk uit te oefenen. Europol waarschuwde in 2022 dat deepfakes een “standaardtool voor georganiseerde misdaad” dreigen te worden. Voorbeelden zijn CEO-fraude (waarbij een vervalste stem of video van een leidinggevende ondergeschikten instrueert geld over te maken), vervalsing van bewijs en productie van niet-consensueel seksueel materiaal.

LLM’s versnellen aanvalsvoorbereiding door automatisch grote hoeveelheden informatie over doelwitten te verzamelen. Ze genereren foutloze phishingmails in meerdere talen en imiteren schrijfstijlen, wat spearphishing veel geloofwaardiger maakt.

Een concrete toepassing is het creëren van synthetische identiteiten met AI. Criminelen gebruiken AI-gegenereerde gezichten en stemmen om zich voor te doen als betrouwbare derden – bijvoorbeeld als helpdeskmedewerker, bankmedewerker of bekende van het slachtoffer. Voice cloning (het klonen van stemmen) is dermate geavanceerd dat in enkele gevallen in 2023–2024 bedrijfsmedewerkers zijn opgelicht door een telefoontje dat klonk als hun directeur, waarin om een spoedoverboeking werd gevraagd. Uit het UNODC-rapport blijkt ook dat ze geloofwaardige valse identiteitsdocumenten of profielfoto’s genereren om verificaties te omzeilen. Dit omvat bijvoorbeeld AI-gedreven ‘identity masking’, waarbij online profileren automatisch worden gerouleerd, deepfake-video’s worden gebruikt tijdens illegale transacties, of het foppen van biometrische toegangscontroles.

Dankzij AI kunnen fraudeurs hun aanpak beter afstemmen op hun doelwitten. Tools kunnen enorme datasets doorzoeken (OSINT) en patronen herkennen om bijvoorbeeld overtuigende persoonlijke babbels of op maat gemaakte phishing-mails te genereren. De Nederlandse politie verwacht dat social engineering-aanvallen de komende jaren verder verfijnd en grootschaliger worden door AI. In het Fenomeenbeeld Online Fraude 2024 wordt expliciet vermeld dat de trend van steeds gerichtere benadering van slachtoffers “vermoedelijk zal versnellen onder invloed van kunstmatige intelligentie”.

Uit een andere analyse van het United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC 2024) blijkt dat criminele fraudenetwerken in Zuidoost-Azië op grote schaal AI inzetten om slachtoffers wereldwijd te bereiken. De onderzoekers zagen een stijging van meer dan 600% van deepfake-content op criminele fora in de eerste helft van 2024 vergeleken met eerdere periodes. Zij combineren bijvoorbeeld gescripte chatbots met deepfake-profielen om geloofwaardige gesprekken te voeren in meerdere talen.

4. AI en seksuele uitbuiting

Een van de meest verontrustende ontwikkelingen sinds 2023 is het gebruik van AI voor het produceren van seksueel materiaal van minderjarigen (ook wel: materiaal van seksueel misbruik van kinderen (CSAM).

Sinds 2023 neemt het gebruik van AI voor het produceren van seksueel materiaal van minderjarigen sterk toe. Politie en opsporingsinstanties zien een duidelijke stijging van AI-gegenereerde afbeeldingen en video’s van kindermisbruik. In Nederland meldde de politie in 2024 dat dit materiaal “steeds vaker opduikt” in onderzoeken. Rechercheurs besteden veel tijd aan het vaststellen of een afbeelding echt is of door AI is gemaakt, wat capaciteit wegneemt van het bestrijden van daadwerkelijk misbruik.

Europol bevestigt deze trend in het iOCTA-rapport 2024: volledig synthetische of door AI gemanipuleerde CSAM vormt een opkomende dreiging.

iOCTA rapport van 2024 op Europees niveau: volledig synthetische of door AI gemanipuleerde CSAM komt steeds vaker voor. ‘Operation Cumberland’ illustreert dit: wereldwijd werden ~270 kopers geïdentificeerd en diverse arrestaties verricht. De Nederlandse politie voerde met vier geïdentificeerde kopers waarschuwingsgesprekken om herhaling te voorkomen.

Nederlandse en internationale politiediensten maken daarbij geen onderscheid in echte of met AI gegenereerde CSAM. Dit is niet alleen omdat de impact (normalisering van misbruikfantasieën) ernstig is, maar ook omdat voor de training van zulke AI vaak echte misbruikbeelden worden gebruikt.

5. Prompt injection attacks

De NCSC UK legt uit dat ‘prompt injection’ een relatief nieuwe kwetsbaarheid is in generatieve AI-toepassingen (ontstaan in 2022). Het treedt op wanneer ontwikkelaars eigen instructies combineren met onbetrouwbare inhoud in één prompt en aannemen dat er een duidelijke scheiding bestaat tussen ‘wat de app vraagt’ en externe data.

In werkelijkheid maken LLM’s geen onderscheid tussen data en instructies; ze voorspellen simpelweg het volgende token. Hierdoor kan een aanvaller via indirecte prompt injection – bijvoorbeeld door verborgen tekst in een CV – het model ongewenste acties laten uitvoeren. Dit maakt prompt injection fundamenteel anders dan klassieke kwetsbaarheden zoals SQL-injectie, waarbij mitigaties zoals parameterized queries effectief zijn.

De NCSC adviseert om prompt injection niet te zien als code-injectie, maar als exploitatie van een ‘inherently confusable deputy’. Ontwikkelaars moeten systemen zo ontwerpen dat ze geen privileges blindelings doorgeven aan LLM’s. Dit betekent: toegang tot gevoelige tools beperken, deterministische beveiligingslagen toepassen en invoer, uitvoer en mislukte API-calls monitoren. Volledige preventie lijkt onhaalbaar, maar het verkleinen van kans en impact is essentieel. Zonder maatregelen dreigt prompt injection dezelfde golf van incidenten te veroorzaken als SQL-injectie in het verleden.